A brief overview of Ukrainian journalism during the war and our projects. Lecture by Texty.org.ua's editor-in-chief

Texty.org.ua, pioneers in data journalism in Ukraine, have changed significantly since the war began. Everything in the media field changed and we want to tell how Ukrainian media landscape looks like since the start of the Russian invasion. Below the lecture of our editor-in chief Roman Kulchynsky in one of European universities.

Journalism in Ukraine during the war

Before the war, journalism in Ukraine was quite well developed, both online media and TV channels. Internet media, as we are, was growing. Still, its financial model remained a significant issue — most relied on advertising.

Only one online media outlet then dared to introduce a paid subscription. At the same time, others feared that readers wouldn't pay since many free news sources were available.

When Russia started its full-scale invasion, dramatic changes took place. The advertising market collapsed. TV channels, which oligarchs mostly owned, also lost financial stability because their owners lost revenue and no longer had extra money to invest in media.

In response, the government introduced a united TV marathon. All major TV channels broadcast the same content, but each was responsible for specific time slots. The government-funded this program and continues to do so now. This seemed logical in the early days of the war, but now it is outdated.

However, the authorities don't want to give it up because controlling the media space is useful for them. While there have been no major scandals about direct censorship, opposition politicians rarely appear on this TV marathon.

This media policy had an unexpected effect—people turned to YouTube for political news. In Poland, for example, YouTube is mostly used for entertainment, but in Ukraine, a significant part of YouTube content consists of so-called "political and military experts" who explain current news and give their interpretations.

The key word here is interpretations.

Most of these people have no real expertise in warfare or politics. However, they tell the audience what they want to hear and attract millions of views. This creates a favorable environment for hidden Russian propaganda because it is often unclear whether these pseudo-experts are simply making things up or if they are being paid to spread certain narratives.

The rapid growth of Telegram channels

Another phenomenon that emerged during the war was the rapid growth of Telegram channels. Telegram is a Russian messaging app that pretends to be international. Before the war, Telegram channels were mainly used by people who were deeply interested in politics because they published different political leaks and insider news. However, they also contained a significant amount of Russian disinformation.

Many Telegram channels became extremely popular at the beginning of the war because they provided information quickly—though often without any verification. Ukrainians were desperate for constant news updates, and these channels met that demand. Later, some were criticized for spreading misinformation, so they verified their content more carefully.

Today, Telegram channels function like new media types, publishing short news updates, fresh videos, photos, and brief commentary on significant events.

One of the reasons why these channels remain popular is their real-time updates on Russian missile and drone attacks.

The Ukrainian Army can track everything happening in the country's airspace. This can be monitored on a special screen available in many military units. So, some people who have access to this app create their own Telegram channels and post real-time updates on Telegram about how missiles and Shahed-drones are moving during attacks:

"A Shahed-drone is approaching Kyiv from the north, moving towards a specific city district."

During air raid alerts, people constantly check these updates to decide whether to go to a shelter, hide behind a "second wall" (the inner wall of the house), or let their families continue sleeping despite the alarm.

People follow these alerts, making Telegram essential to their daily routine. However, it is unclear what other content they consume on Telegram since the news feed is long, and few people read everything.

Although some professional journalists work for Telegram channels, it isn't considered respectable. These channels still contain a lot of unverified news and hidden paid content.

Professional online media outlets

The most high-quality segment of Ukrainian journalism consists of professional online media. Some introduced paid subscriptions during the war, others stabilized their advertising revenue after the initial shock, and some found investors who supported them with the hope of profiting or selling the media after the war. Many also receive grants from international donors, primarily USAID. As you know, USAID stopped working after Trump won the election.

Some investigative teams publish their work mainly on YouTube. They have their own websites, but YouTube is their primary platform. They earn money from YouTube monetization, advertising, and sometimes grants from USAID or the EU. These teams usually specialize in anti-corruption journalism. However, since the war began, some have shifted to military reporting, investigations of Russian war crimes, or uncovering espionage stories.

The Kyiv Independent

An interesting example is The Kyiv Independent, an English-language Ukrainian media outlet. Just before the war, its editorial team split from its previous employer due to attempts at censorship. They all quit and founded their own media outlet.

When the war started, they gained a massive international audience by providing fast, high-quality reporting in English. Within weeks, they built a strong base of private donors worldwide who continue to support them financially. This is a unique and very successful case.

In addition to articles, they produce high-quality documentary films about the war.

War Reporting: Text vs. Video

Ukraine has many video reports from the frontlines but few high-quality text reports. It is unclear why — perhaps the audience prefers videos, or writing a strong text report is harder than producing a dynamic video.

Some journalists become upset with their profession and join the Army, believing they can contribute more as soldiers. One of my friends, an exceptional war reporter, initially covered the war with in-depth reports but later joined the Army. Only a few people can write compelling war stories. Some work as assistants for Western journalists because it pays much better than working for Ukrainian media.

Ukraine's Public Broadcasting Service

One of Ukraine's best media outlets is Suspilne (Ukraine's Public Broadcasting Service). It includes several TV channels, national radio stations, and regional newsrooms. Although the state budget funds it, its editorial policy remains independent due to an independent supervisory board.

However, Suspilne always struggles with a lack of funding. Although it has received support from international donors, its situation has worsened when USAID funding cuts. Despite financial challenges, Suspilne produces excellent documentaries about the war.

Military Censorship in Ukraine

Surprisingly, Ukraine has almost no military censorship. The media can criticize generals and government officials. The main restrictions are:

- Filming or photographing the movement of military equipment and frontline positions is forbidden because Russian forces monitor everything online, even from distant sources. Such images could help them adjust their attacks.

- It is prohibited to photograph air defense operations, as this could reveal the positions of air defense systems.

- Live-streaming from public places is banned to prevent the enemy from gathering intelligence in real-time.

Although no official censorship exists, journalists often face bureaucratic challenges in obtaining accreditation to work on the frontlines. Sometimes, it takes a long time, and accreditation might even be ignored at military checkpoints. However, good personal connections with military commanders on the field can solve many problems. The downside is that journalists may feel pressured not to criticize these commanders, fearing losing access in the future.

How important it is to have direct links with combat units is shown by the fact that, despite the existence of permits from Kyiv, Ukrainian and international journalists managed to enter Russia's Kursk region behind Ukrainian troops after Ukraine's incursion in it.

But you need to know that Russian authorities responded aggressively, launching criminal cases against those who crossed the border in this way and organizing online harassment campaigns against them.

In the last months, the Ukrainian Army has tightened control, and it is practically impossible for journalists to get into the occupied part of the Kursk region.

Our projects during the war

Now it's time to talk about our media outlet, Texty.org.ua.

We are a small newsroom that specializes not only in traditional articles but also in data journalism.

It's often difficult to explain to people who don't follow our work what exactly we do because many confuse data and facts. Of course, data is also a form of facts, but collecting data is not the same as gathering facts for a traditional article.

By data, I mean thousands of rows in a spreadsheet. For example, to check if stores trick customers during Black Friday sales, we scraped prices from various online shops six months before the sale and compared them to the discounts offered on Black Friday. Our conclusion? Many so-called discounts were fake — the "discounted" price was just regular.

To understand what narratives Russia was pushing, we downloaded news articles from hundreds of Russian sources over a week and used algorithms to determine which topics were the most common.

You need technical and journalistic expertise to work with this kind of data. In today's world, an enormous amount of data is available, and if you know how to collect and analyze it, you can describe reality in a much more precise way. That's exactly what we do.

I want to share some of our projects and explain how and why we created them — from the initial idea to the final product.

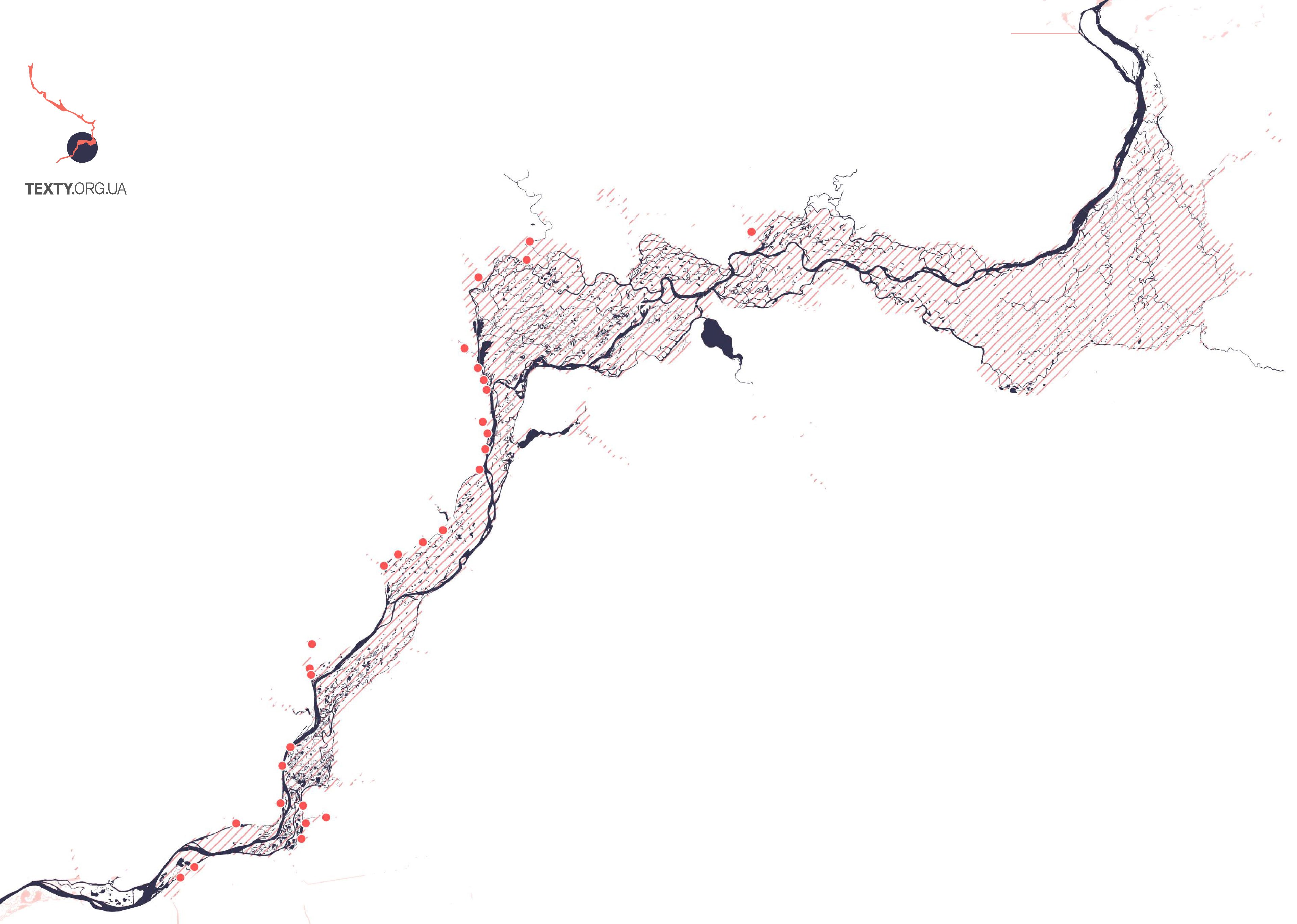

The air war: The routes of "Shahed" drones and missiles during September-October

Earlier, I mentioned how Telegram channels track the routes of Russian air attacks. We decided to visualize this data and create a project based on it.

These are the attack routes for the two autumn months of 2023. Yellow indicates the routes of Shahed, red indicates cruise missiles, and blue indicates ballistic missiles.

This project, published in December 2023, attracted the interest of a few international media outlets, and some even asked us for access to our data.

Unlike missiles, Iranian drones Shaheds are much cheaper but carry less explosive material. Russia frequently uses them to attack Ukrainian cities and energy infrastructure.

The most interesting question is, where did we get the data?

As I mentioned earlier, Telegram channels publish real-time updates about drone movements. Like many Ukrainians, I followed these updates. At some point, I thought, "What if we put this information on a map?" The next day, we started working on it.

However, this was a very time-consuming task, and the routes were far from precise. Our first visualization was quite simple, but it was already the first attempt to show these attack routes in a structured way.

Approximate route of the "Shahed" on the night of September 20

One of our first visualizations on this topic is the Shahed attack on 20 September 2023. This is a regular attack without a challenging route and a few drones.

After we published this first map, one of the monitoring channels contacted us and offered more accurate data. We agreed to collaborate. It was impossible to verify the information, but in general, it matched:

- The official statements about air attacks;

- Reports from other monitoring channels;

- What our own team members observed.

We continued visualizing this data for about two months, and the maps became popular. However, higher military officials noticed our project and the collaboration ended. At the same time, other Telegram channels started creating similar maps.

Unfortunately, Ukraine's General Staff does not always understand the value of information and prefers to classify everything. However, in this case, we were not revealing any military secrets — the enemy already knows which routes their own drones and missiles take. Also, all the details were very simplified at the large scale of our maps.

Ultimately, we combined all the attack routes we had visualized over two months into one final map.

How Shaheds and missiles flew during the massive attacks on March 23-24

This was one of the complex, combined attacks that occurred a year ago on 25 March 2024, when the Russians targeted a gas storage facility in Western Ukraine. The site holds reserves for Ukraine's winter needs and also serves as a storage location for some Western companies. Despite the attack, it remains operational. I don't know whether international companies continue to store gas after such attacks.

The Path to the Sea

Another project I want to discuss is our investigation of Russian defense structures — the fortifications they built before Ukraine's counteroffensive in the summer of 2023.

In the media, there were many fragmented reports about these fortifications. There were dozens of news updates every day, but people were losing track of the bigger picture. So, we decided to show what was really happening on the ground and what Ukrainian forces were up against.

Since we didn't have the resources to send a reporter to the front line but had the skills to analyze large-scale data, the solution was obvious — use satellite images.

Another challenge was that the front line was extremely long, making it impossible to show every Russian position. The obvious choice was to focus on one key battlefield — the area near Robotyne, where the most intense fighting was happening.

It was also important to show the depth of Russian defenses of all three defensive lines.

So, we collected satellite images from Planet Labs, explored them, and identified enemy positions, fortifications, and supply routes.

However, satellite images alone can look boring — especially compared to the dramatic videos people see in the news. So, we decided to add something extra.

To make the project more engaging, we used an old Soviet military manual, which contained diagrams of fortified positions. We recreated these diagrams in our own style and used them to explain how Russian defensive positions were built in reality.

Of course, we didn't map out every trench — that would have been too overwhelming for the readers. Instead, we selected the most typical examples.

One data journalist and our art director completed the entire project. The journalist downloaded the images, analyzed them, marked the fortifications, wrote the text and assembled the entire project.

A Wall of Fire

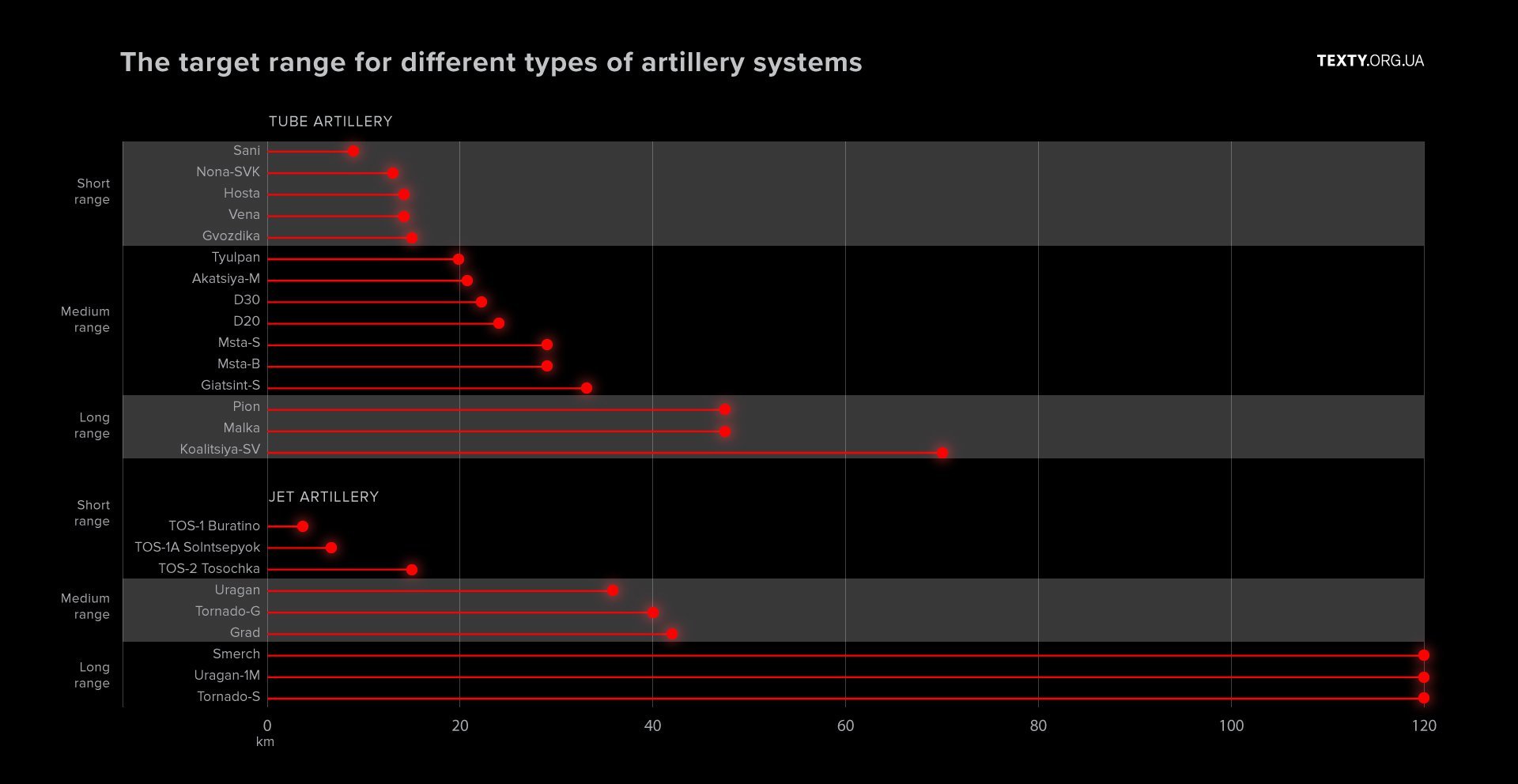

Another project we worked on was "A Wall of Fire," which we published in July 2022.

At that time, the Ukrainian Army had just liberated part of its territory, but Russian forces were trying to launch new offensives. Russia had plenty of artillery and ammunition, while Ukraine's artillery resources were limited.

The Western allies — especially the United States — were still hesitant to provide heavy weapons, fearing escalation with Russia.

Since Ukraine lacked the resources for counter-battery fire, Ukrainian soldiers often had no choice but to hide in trenches and endure the shelling. The Russian advance failed, but many of Ukraine's most experienced troops were lost.

We noticed that news reports at the time were very fragmented. There were occasional stories about Ukraine's lack of artillery, but few people understood how massive the Russian artillery fair was.

Once, a war reporter brought us a letter from a Ukrainian soldier to his granddaughter, describing one day under intense shelling. That's when we created a data visualization to show what it was like under Russian artillery fire.

We used statistical data on shelling to calculate the number of shells that could land on a single frontline position in just one minute. The numbers were approximate, but they helped show the scale of the attack.

Then, we created a simulation of artillery strikes on a fictional Ukrainian position.

Red dots showed where shell fragments landed, marking the area of the impact zone after a shell explosion. Large squares represented rocket artillery barrages, highlighting the zone hit and burned by a rocket salvo.

To add realism, we also included actual audio recordings of artillery strikes. We carefully searched for real battlefield sounds to match different types of shelling.

Along with the visualization, we added a video of Grad rocket attacks — both from a distance and from the soldiers' perspective inside the trenches.

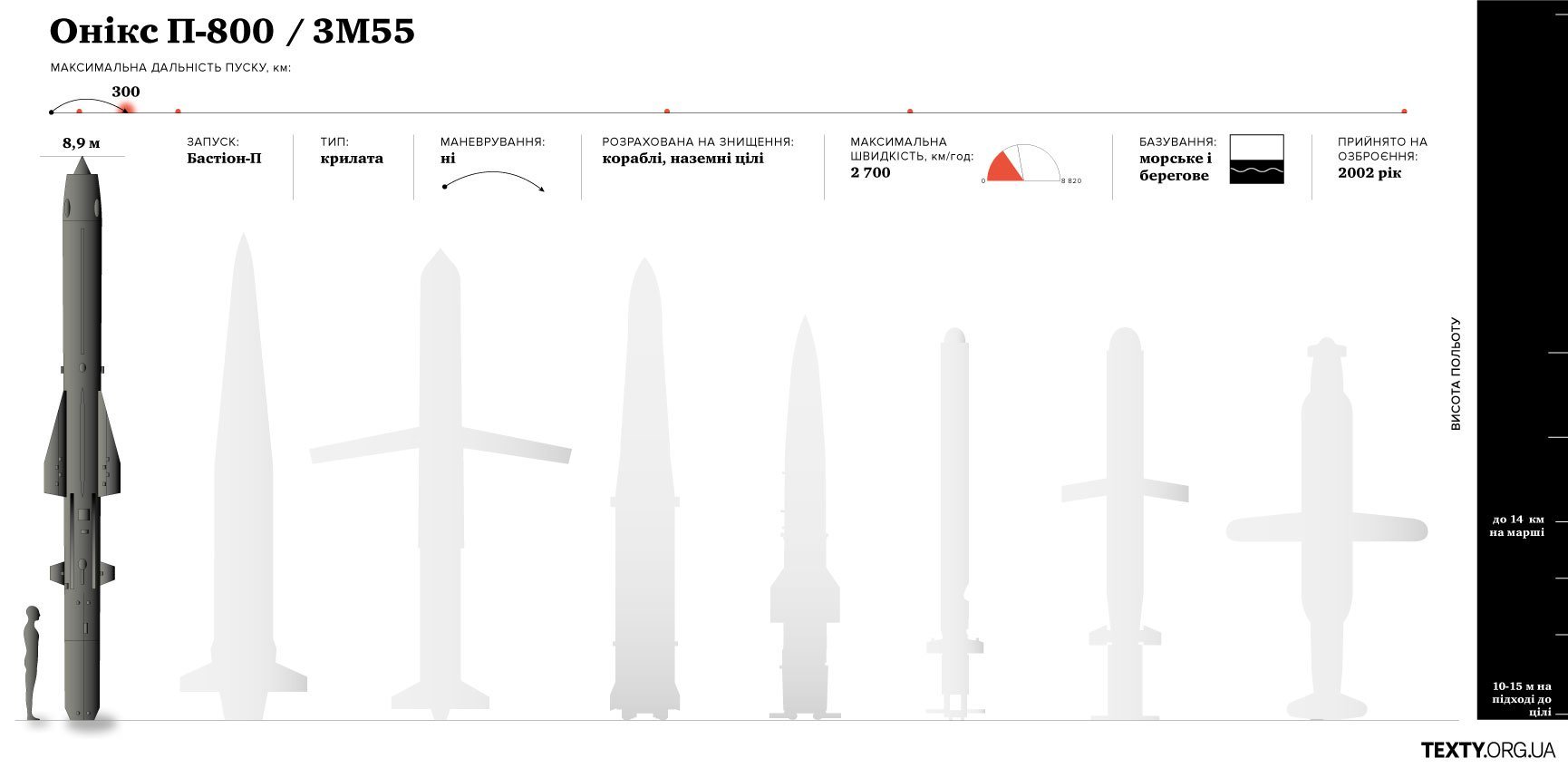

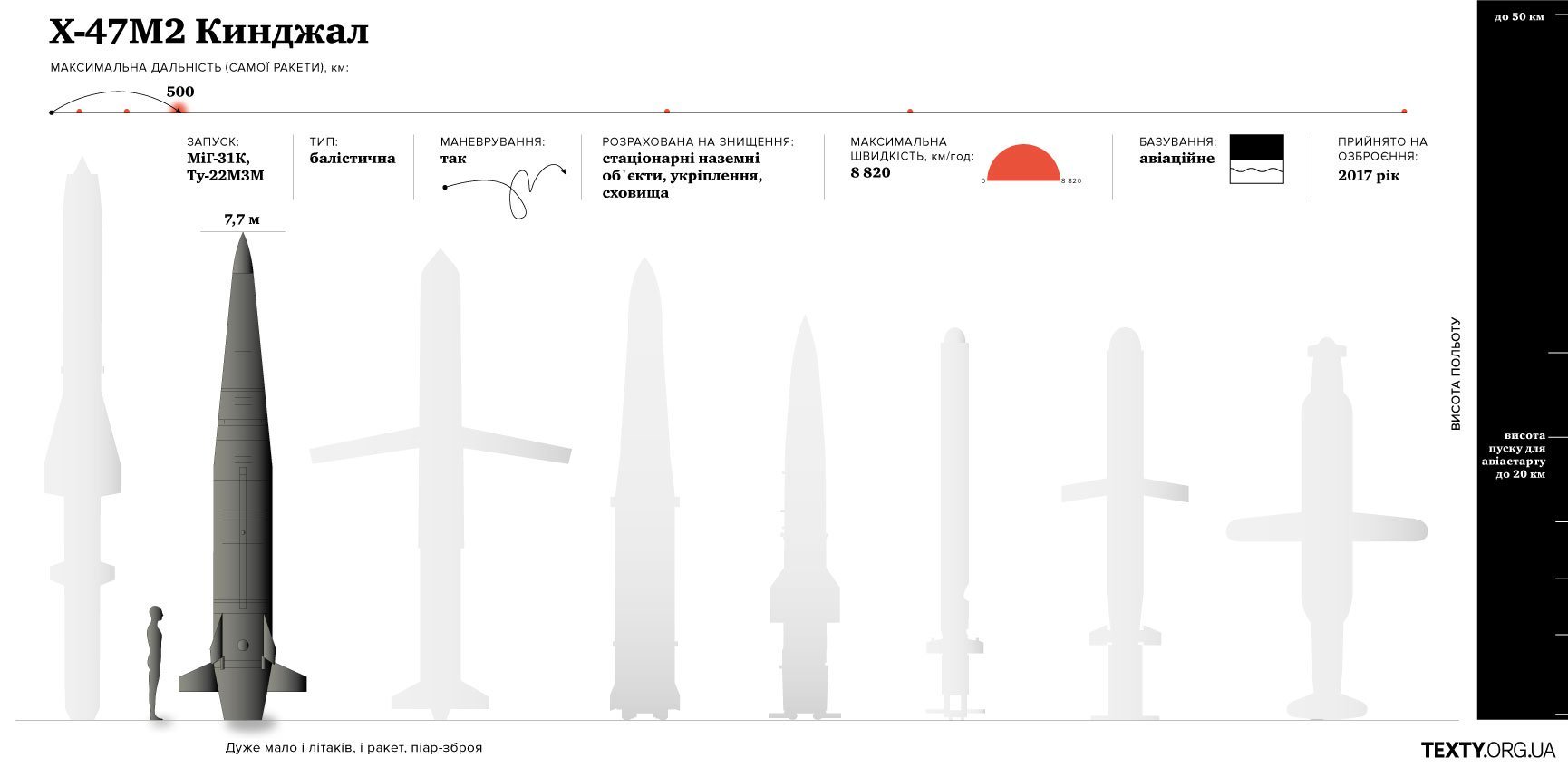

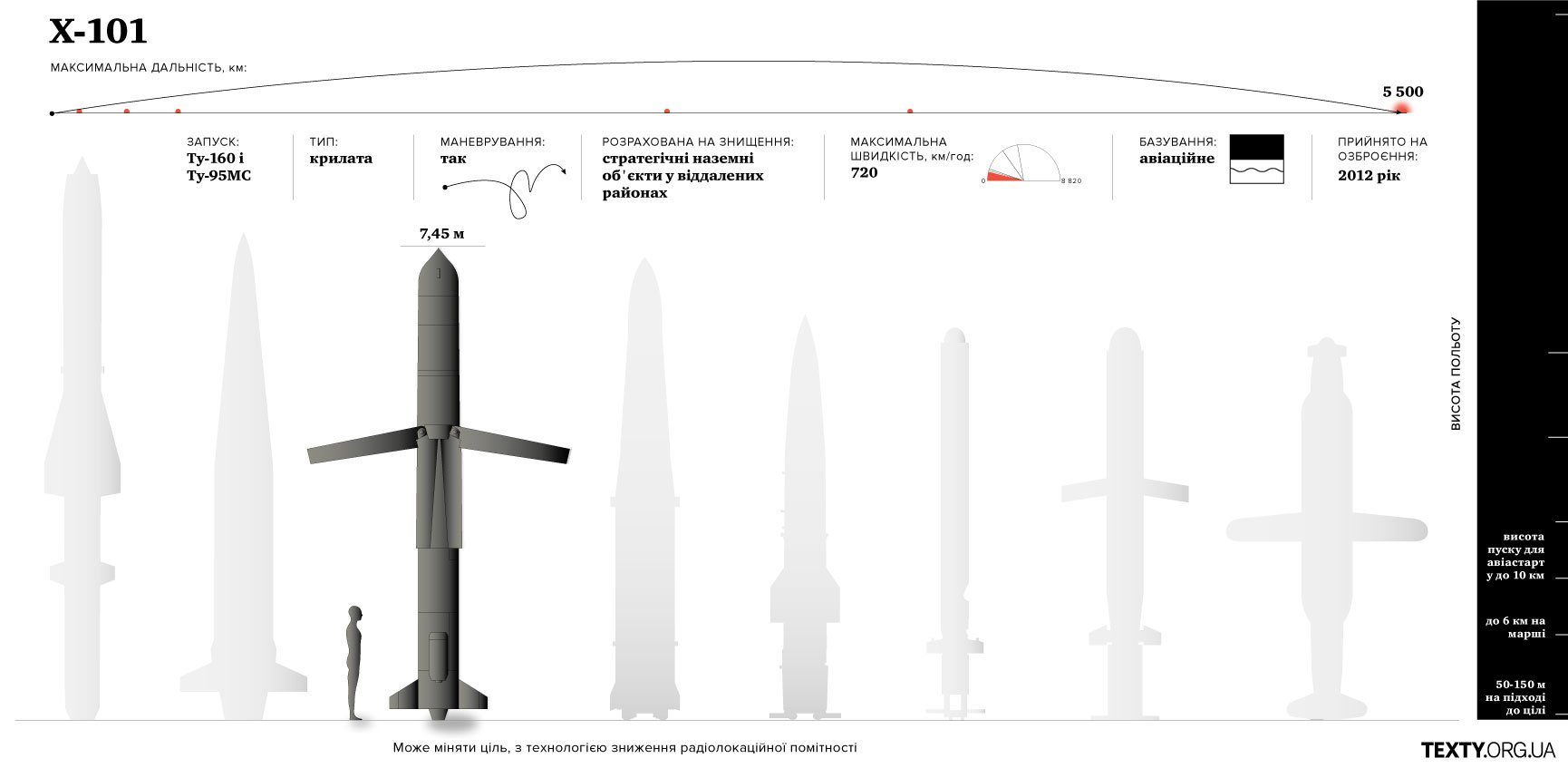

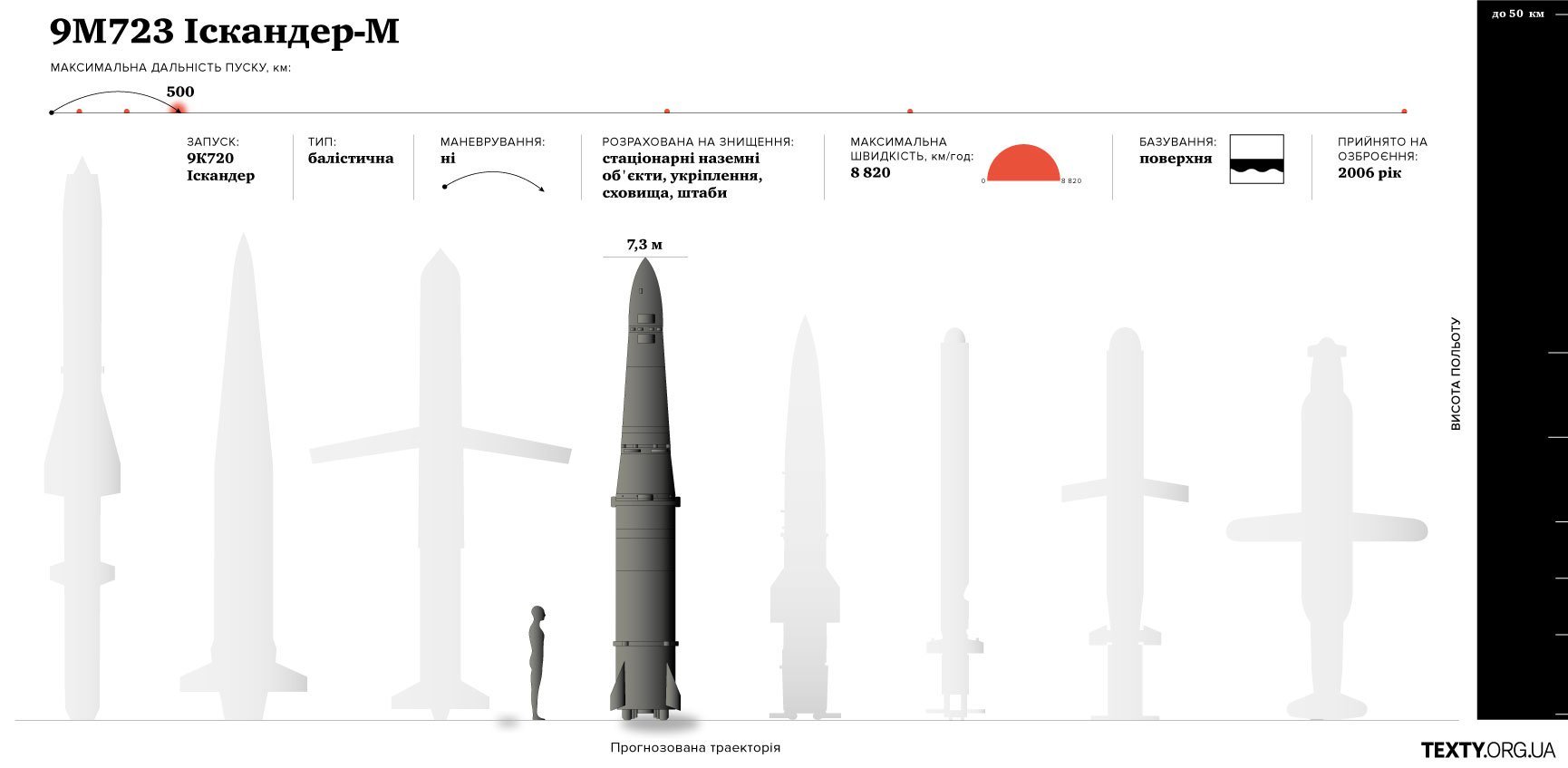

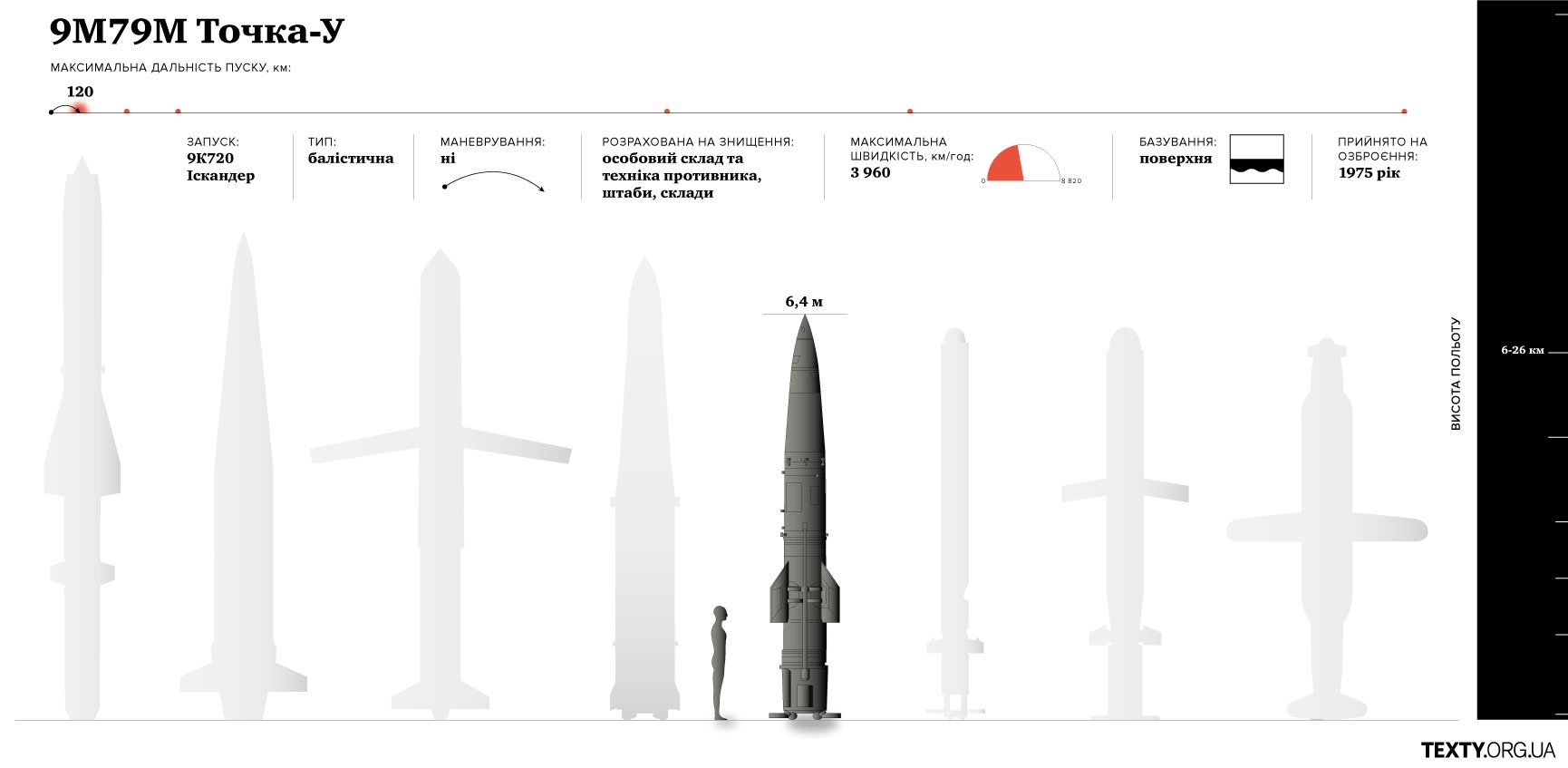

Flying Death. Everything about Russian missiles

This was one of our first war-related projects, created in the early months of the full-scale invasion. At that time, the entire country was shocked by Russia's missile attacks, and readers wanted to understand what kinds of missiles were being used, how they flew, and how they were launched.

Our audience has always been interested in details. Missile specifications were always available in open sources. However, before the war, no ordinary person would have even thought to study them. No one believed these weapons would ever actually be used.

So, we decided to illustrate different types of missiles, show their characteristics, and collect videos of launches and their impact sites.

Today, unfortunately, this has become a routine topic. It's no longer surprising to hear Ukrainian women in supermarkets discussing which missiles Russia launched the night before, so projects like this are no longer as relevant.

Working with maps

We also love working with maps. Unfortunately, war has provided many reasons for its creation. I'll highlight just a few examples.

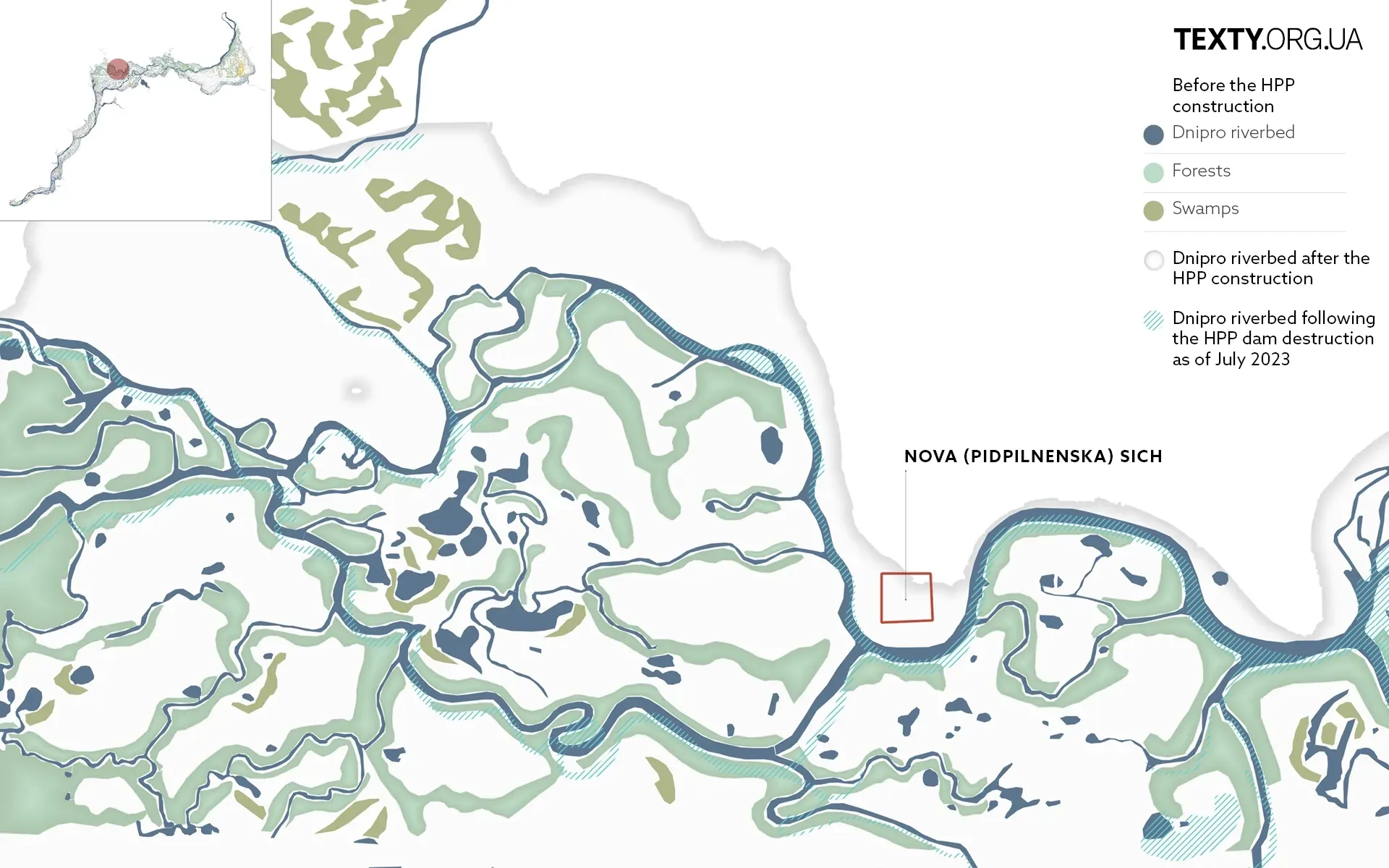

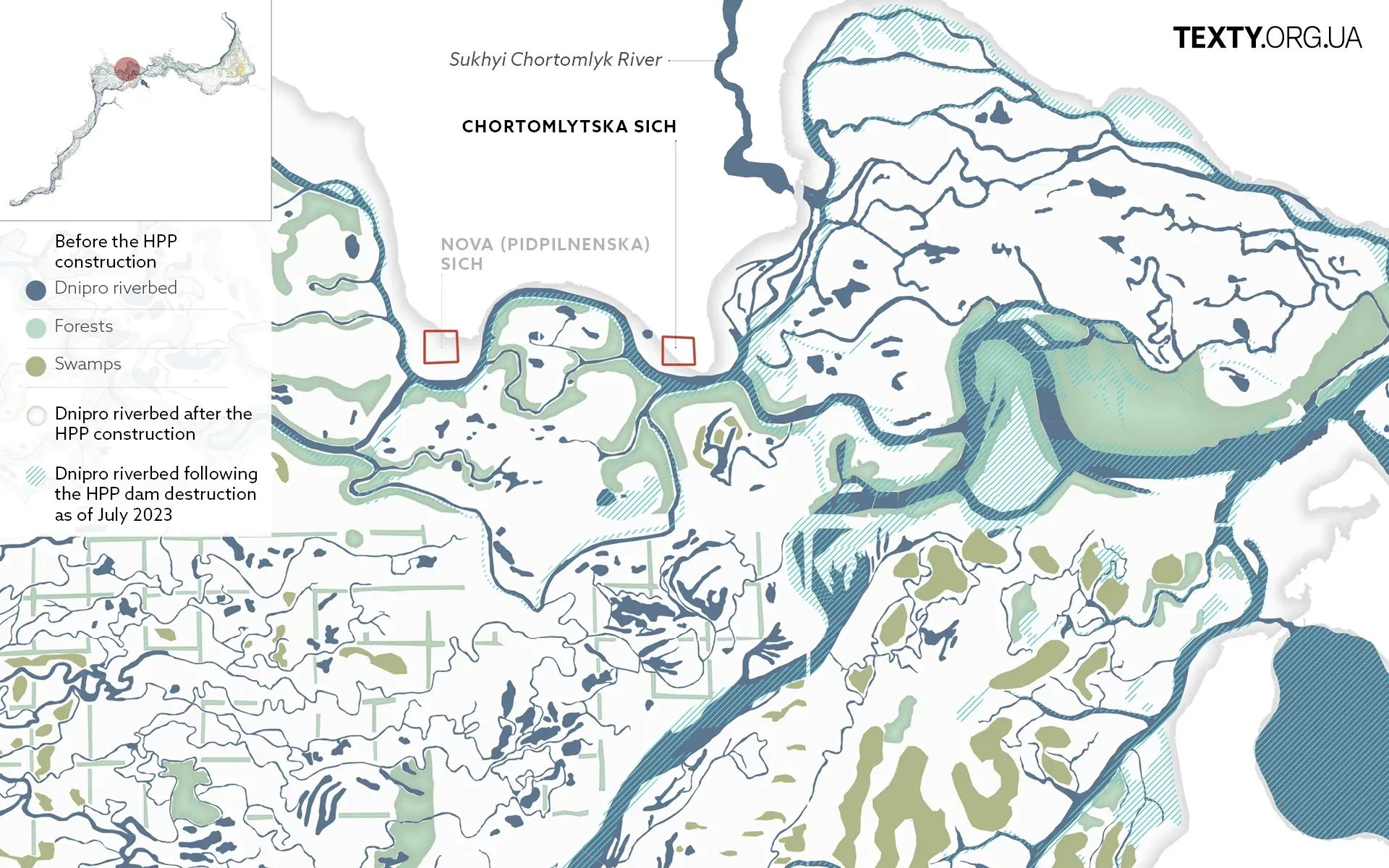

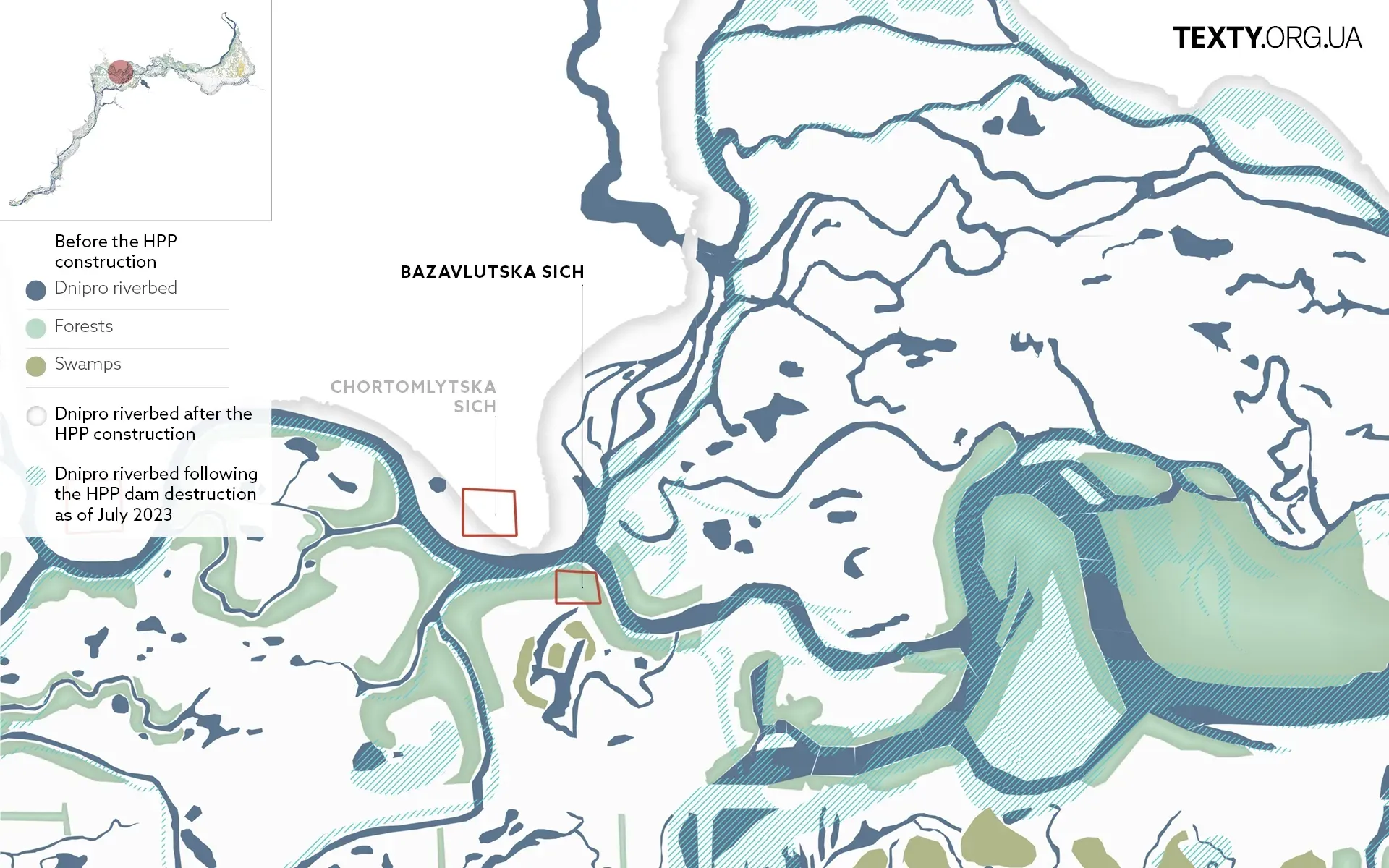

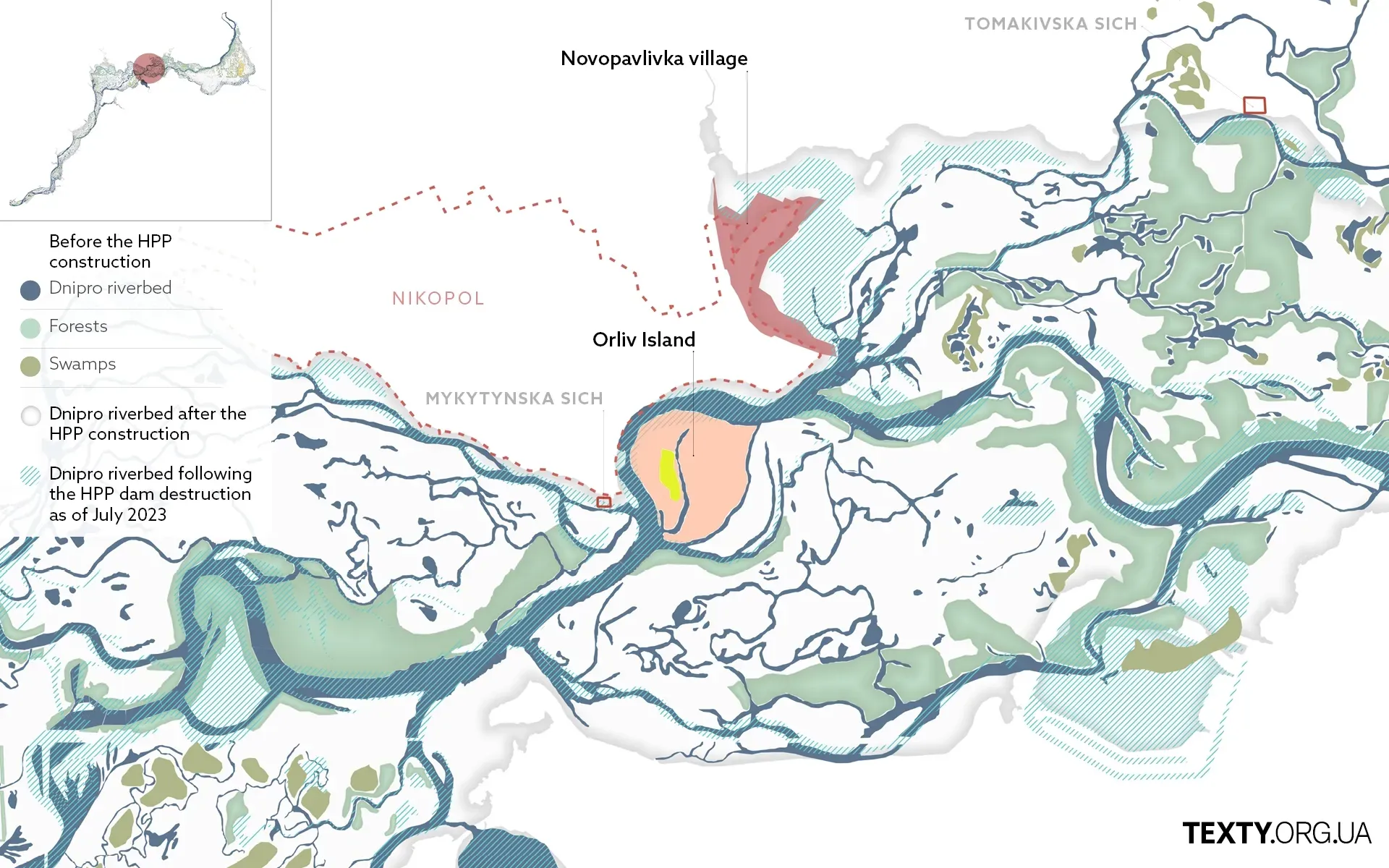

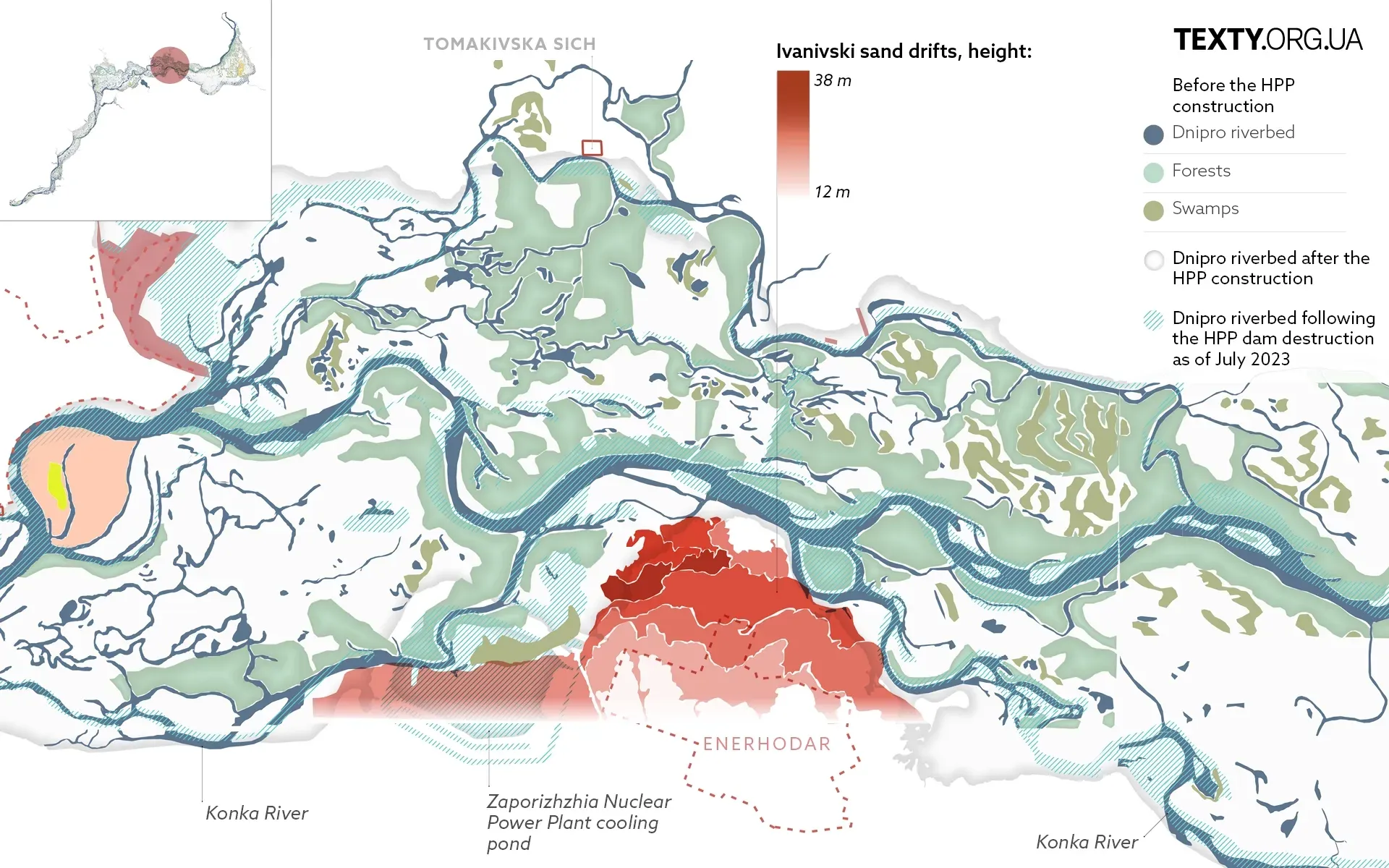

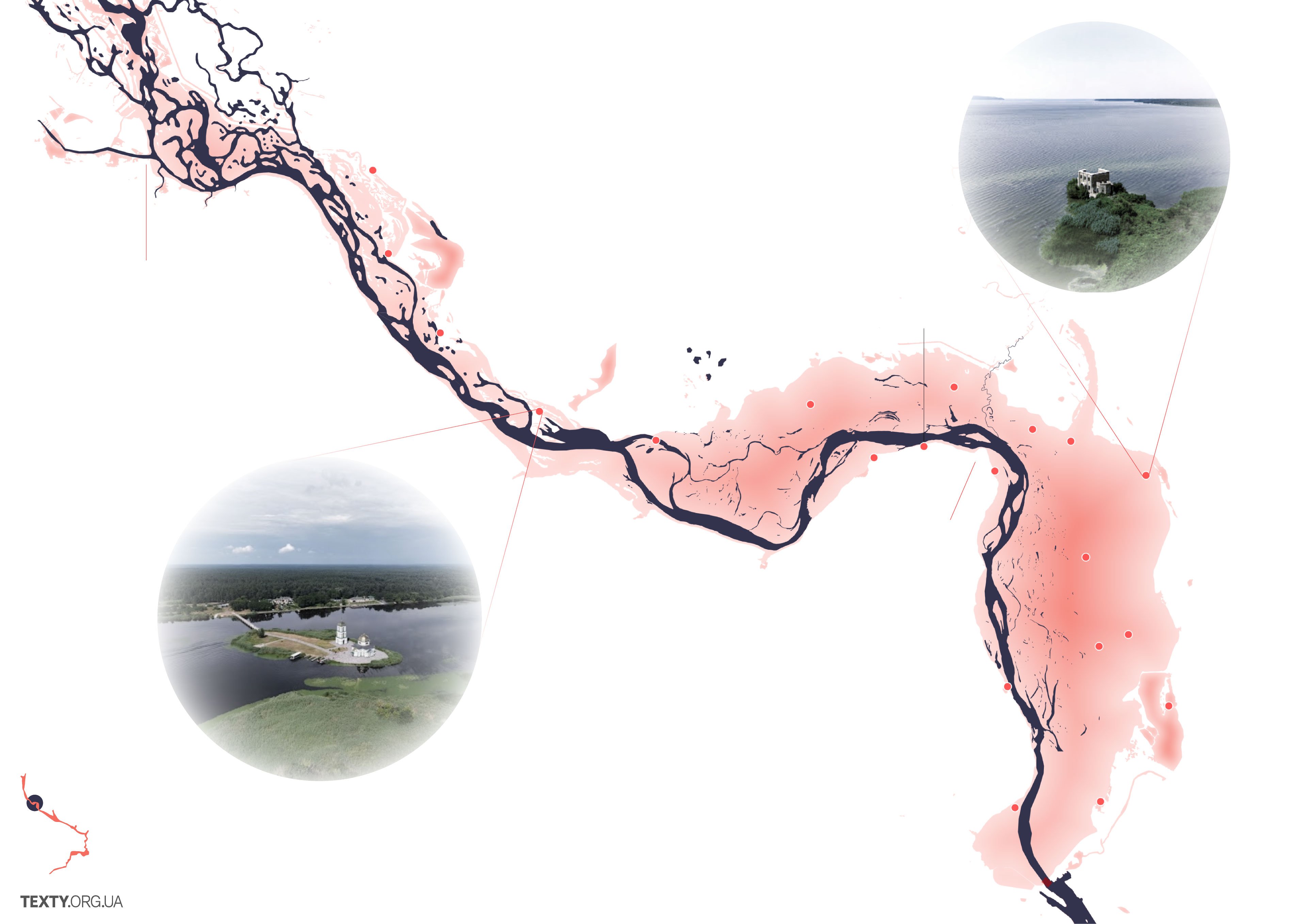

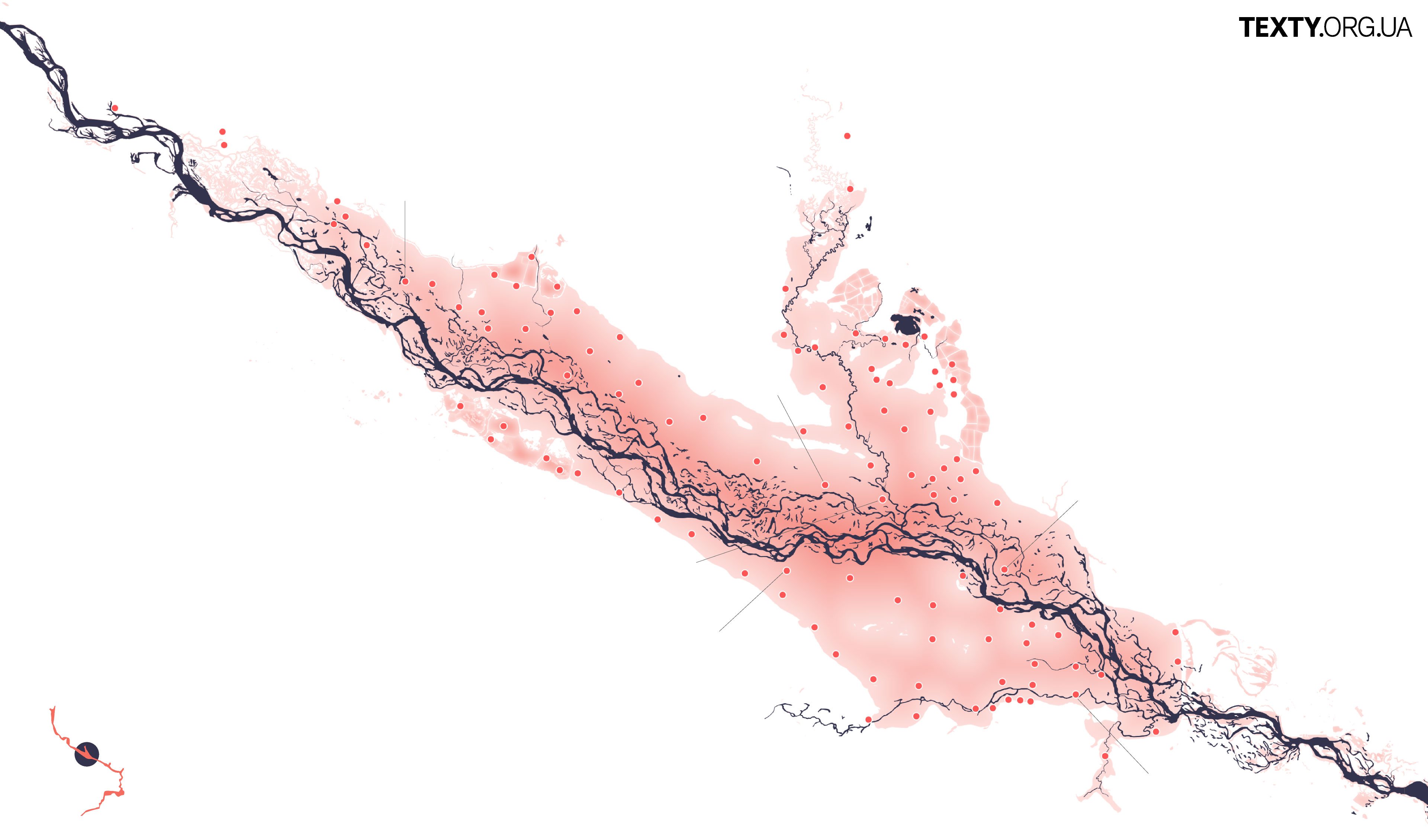

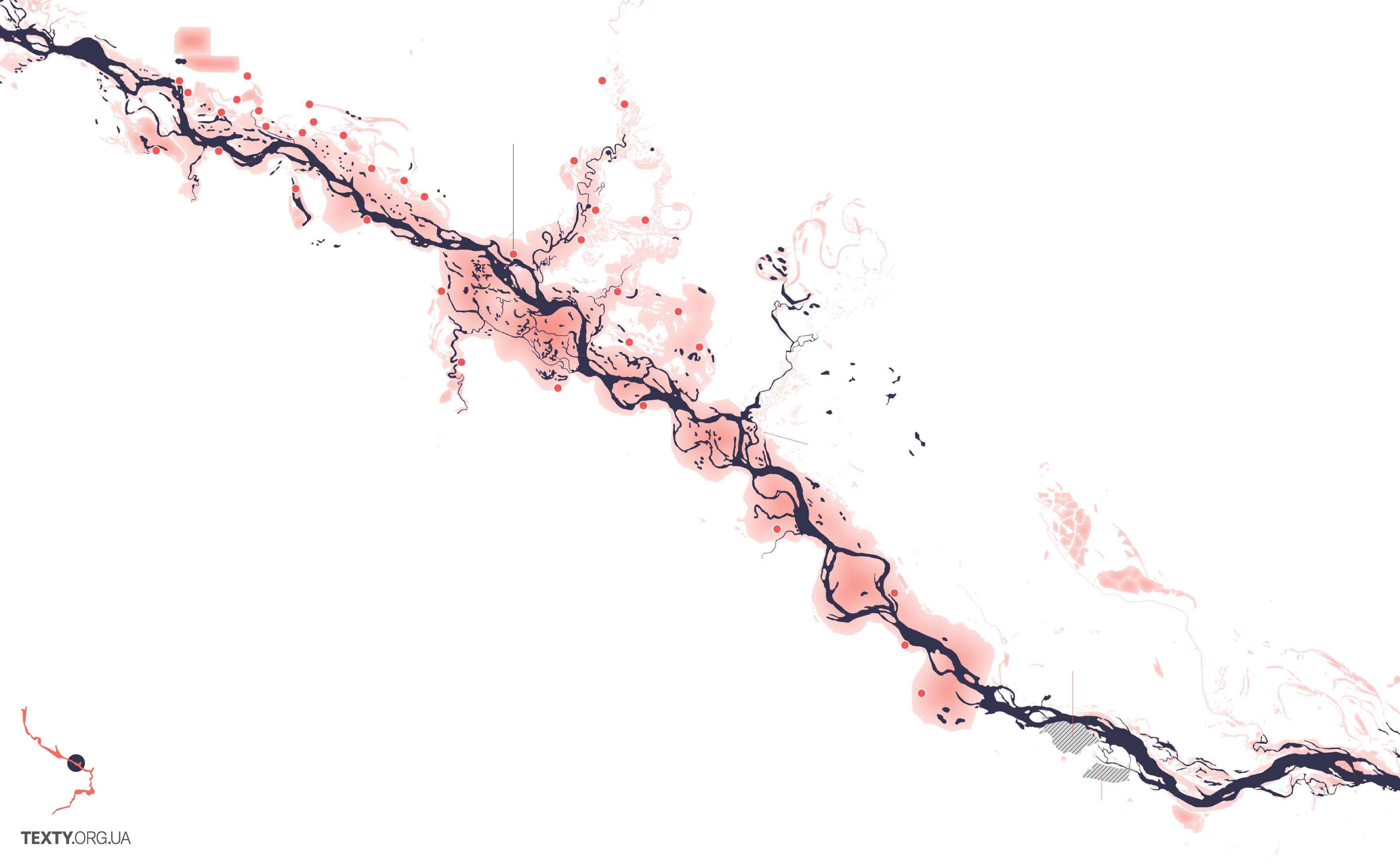

In the summer of 2023, Russian forces blew up the Kakhovka Dam on the Dnipro River. The Dnipro is a massive river that flows from north to south across Ukraine.

During the 20th century, the Soviet government built seven dams along the Dnipro, causing irreversible ecological damage. This not only flooded historic sites important to Ukrainian history but also wiped out the remnants of traditional life in local communities.

For example, Zaporizhian Sich, the historical stronghold of Ukrainian Cossacks, was located on islands that are have been became underwater. This would be like demolishing the ancient center of Athens in Greece just to build an industrial project.

We have also worked on a project about this topic, but I will talk about it later. Let's first return to the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam.

What happened to the Kakhovka Dam?

This dam was the last in the cascade along the Dnipro. The explosion happened just before Ukraine's often announced counteroffensive. And there is widespread speculation that Ukrainian forces had planned to cross the river to bypass Russia's well-fortified positions.

Whether this was truly the plan is unknown, but one thing is clear— Russia destroyed the dam.

Of course, Russia denies responsibility and has spread various disinformation narratives. Some Russian sources claim that the dam collapsed due to gradual wear and tear, while others insist that Ukraine blew it up itself.

We spoke with a Ukrainian expert on dam construction, who has spent his entire career designing such structures. He explained that Soviet-built dams on the Dnipro were engineered to withstand a nuclear strike. This means that the only way to destroy the Kakhovka Dam was from the inside. And only Russian troops were able to enter the inside, they controlled the part of the dam where the entrance was.

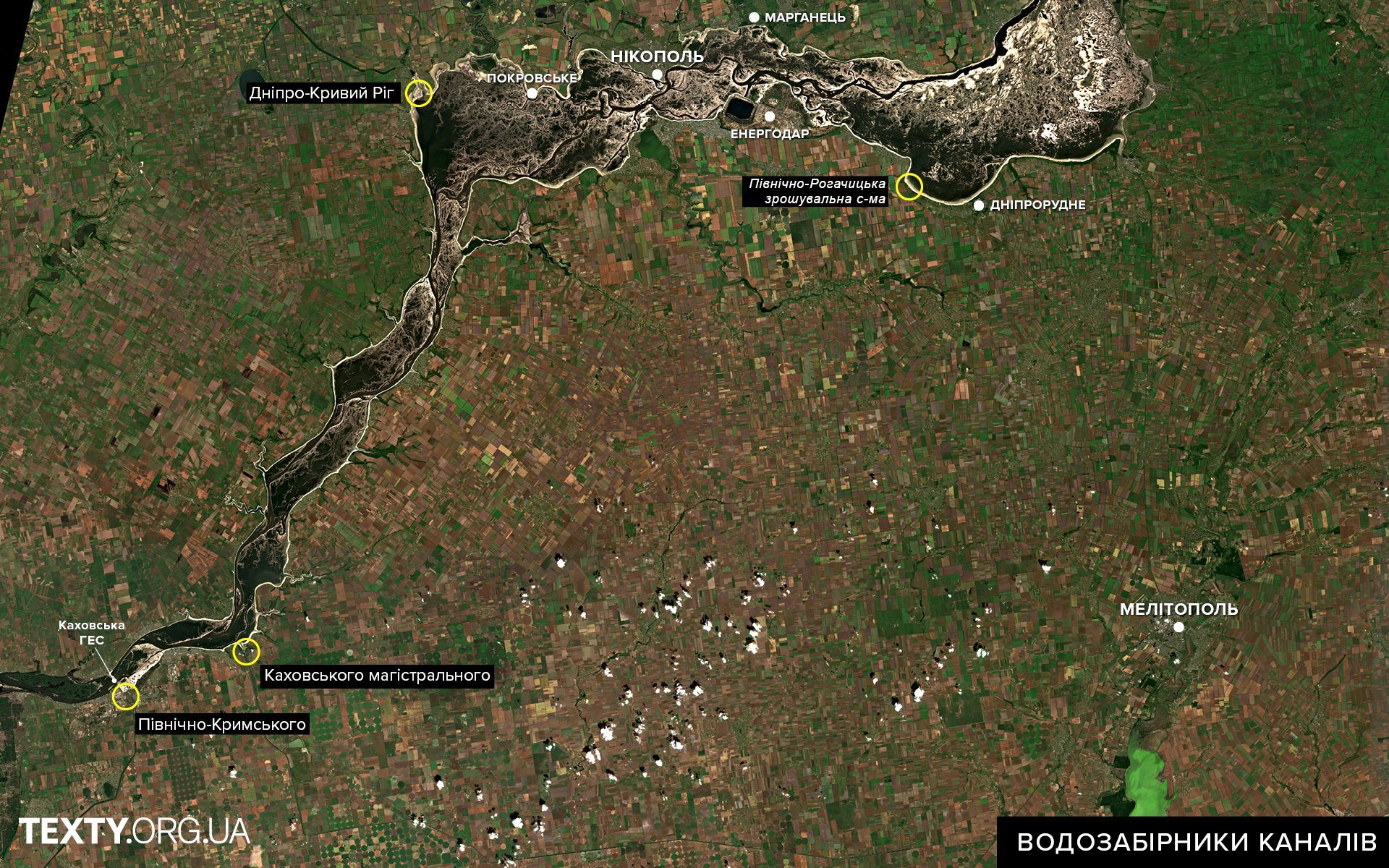

How did the Dam's destruction impact the region?

We tried to show how this disaster affected daily life. The entire region's water supply, agriculture, and industries were dependent on the Kakhovka Reservoir.

This map shows where water was drawn to supply major cities and farmers.

Here is a satellite image of the Kakhovka Reservoir one month after the dam was destroyed. The black areas represent remaining water.

In this map, you can see:

- Irrigation canals that used to take water from the reservoir.

- Soil humidity levels after the destruction.

- Dark blue areas, which represent water that remained in the former reservoir.

- Light blue areas, which show where water disappeared.

The destruction of the dam was a topic of huge interest to our readers, and we published many articles about it.

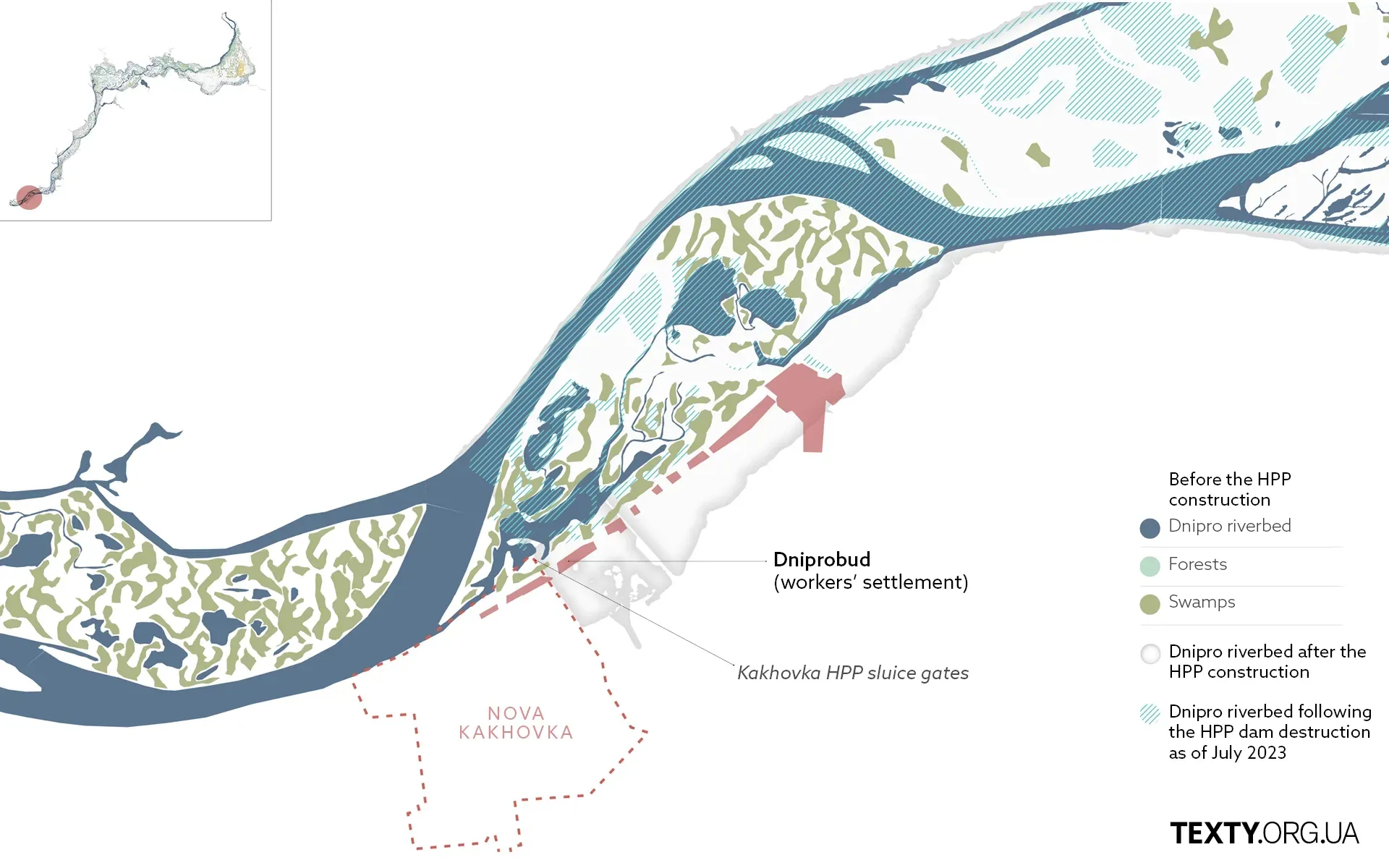

Velykyi Luh: Map of the Great Meadow

One of our later projects involved overlaying historical topographic maps from World War II onto modern satellite images. This allowed us to compare what the area looked like before the Kakhovka Reservoir was created and how the landscape changed after the dam was destroyed.

In this map:

- The solid blue areas represent the Dnipro River and its tributaries before the dam was built.

- The lightly shaded areas show where water remained after the explosion.

We wanted to highlight how unique the natural ecosystem was before Soviet communists flooded it. This was also relevant because the Ukrainian government announced plans to rebuild the Kakhovka Dam after the war. At that time, many believed the war would end soon, so we wanted to raise public attention about the possibility of restoring the natural environment instead of reconstructing the dam.

From a technical perspective, overlaying old maps with modern satellite imagery required a lot of tedious work, but we chose to invest our resources to make it happen.

We also did many field reports about the flooding caused by the dam's destruction. Our team contacted by phone locals whose homes were submerged, some of whom had to take shelter on their rooftops to survive.

The situation was even worse in the occupied territories. Ukrainian-controlled areas were located on the higher bank of the river, while Russian-occupied areas were on a lower bank. When the floodwaters rose, Russian forces abandoned the local population. Ukrainian emergency services were unable to reach them because Russian troops kept shelling rescue teams. In some cases, drones were the only way to deliver food and water to stranded civilians.

230 flooded villages. What the old Dnipro riverbed before and after the flooding

Later, we created a map showing the entire course of the Dnipro River as it looked before the Soviet dam system was built.

These are just examples of how we use data, maps, and visual storytelling to document the consequences of war and historical changes in Ukraine.

Projects on Russian disinformation

A significant part of our work is investigating Russian disinformation. Ukraine has been dealing with it for a long time. I'll tell you about some key projects in this area.

One of my favorite projects is our first significant investigation in this field. It was published eight years ago.

It all started when we found an article on Ukrinform, a Ukrainian news agency. The story described how hackers had leaked the emails of a well-known far-right Ukrainian online activist named Stepan Mazura. The emails revealed something shocking — this so-called "Ukrainian patriot" actually lived in Moscow.

In other words, Stepan Mazura was a fake identity carefully constructed on Facebook. His posts encouraged Ukrainians to take to the streets, calling for a new Maidan revolution and even urging people to overthrow then-President Poroshenko by force. He used patriotic slogans, making it seem like he was an ordinary Ukrainian nationalist.

We decided to investigate further. We looked at the Facebook groups that Mazura managed, checked who else was listed as an administrator, and then traced the networks of groups these people controlled. What we uncovered was an entire ecosystem of "patriotic" Ukrainian Facebook groups — all spreading narratives that were created in Russia.

Surprisingly, these groups weren't run solely by bots and Russian-based admins. Many real Ukrainian users had joined these communities and believed in the narratives being pushed. They were just ordinary people who absorbed and shared Russian disinformation without realizing it. Russians have a term for such people — "useful idiots," and there were many of them.

This Russian disinformation concerned the internal political life of Ukraine, it did not glorify Russia. It sought to create divisions within Ukraine and turn active citizens against their state. This was when the first phase of the war against Ukraine, which began in 2014, was ongoing.

Then, we noticed another important pattern. These groups constantly posted links to low-quality websites—obscure, trashy news sites that published fake stories and Kremlin-friendly interpretations of events. We analyzed the total monthly traffic of these so-called "junk news" websites and discovered that their combined audience was comparable to Ukrainian Pravda, one of the most popular mainstream Ukrainian media outlets.

When we published our findings, a major reaction occurred. At the time, many people in Ukraine were already discussing Russian propaganda, and efforts to counter it were underway. However, journalists, experts, and even government officials still didn't fully understand how Russian disinformation was structured or tailored to different audiences.

By the way, this tactic of creating low-quality websites and spreading their links through targeted Facebook groups is a proven Russian method, and it still works today.

Not long ago, the FBI exposed Doppelganger, a Russian disinformation campaign in the USA and Europe. This campaign focused on spreading links to fake websites, although the websites were disguised as well-known media this time.

"We Have Got a Bad News"

Our next step in studying Russian disinformation was a project called "We Have Got Bad News," in which we analyzed the narratives spread on the previously mentioned junk news websites.

At that time, the first AI-powered language models were just emerging—the kind that would later evolve into big language models like ChatGPT. We decided to use this new technology to analyze the narratives being pushed by these junk news websites.

At the beginning of our study, we invited the editors who work with news on a daily basis. With their help, we defined and described the most common types of manipulative news:

- First, "a complete fake."

- Second, "A manipulative headline/clickbait"

- Third, "A conspiracy theory / Pseudoscience."

- Fourth, "Emotionally biased news."

- Fifth, "Wrong arguments."

- Sixth, "Political conspiracies"

- Seventh, "A normal text."

Then, we downloaded around 10,000 news articles from junk websites and well-known websites with good reputations. After that, we marked each piece of news as either "normal" or "corresponding to one of the manipulative types." We studied only the news about Ukraine's political and social life, omitting entertainment, sports, celebrities, etc.

After that, we trained the deep learning algorithm to define the types of manipulations in the news. While conducting our work, we found that the most common types of manipulations are "emotional bias" and "wrong arguments."

The algorithm was wrong in less than 8 percent of the cases when defining manipulative news from normal ones. On a large amount of data, such a percentage of errors allows us to rank websites relative to each other.

Next, we grouped similar narratives together, which helped us see the bigger picture — what kind of worldview these websites were trying to promote among Ukrainians.

Simply put, the Russians painted a picture of the world in which Ukraine was collapsing, highly corrupt, its people extremely poor, and ruled by external forces from the West. That's why we called our project We Have Got Bad News. All the pieces that these sites produced sowed complete hopelessness.

This project took us nine months to complete. We were extremely lucky to secure a grant for this research, which became the foundation for a whole new direction of work in our newsroom.

However, securing funding for this kind of project wasn't easy. At that time, international donors still didn't fully understand how hidden Russian disinformation operates. Many people thought propaganda was obvious, like Russian TV channels praising Putin. But the reality was much more complex and dangerous. Russian disinformation was designed to destabilize societies from within, and our project helped prove that point.

A change of pace – Investigating nature instead of war

Last summer, after working on so many war-related investigations and projects on Russian disinformation, our team needed a break.

We wanted to create something beautiful for a change, so we started working on a project about how nature is reclaiming the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone.

Nearly 40 years ago, around 2 thousand 5 hundred square kilometers of land became uninhabitable due to the Chornobyl nuclear disaster—the worst nuclear catastrophe in human history.

It led to the largest peacetime evacuation ever, forcing entire communities to leave their homes and industries to shut down.

But despite everything, the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone never became a wasteland. Over the years, as people left, nature returned.

And what about now?

Last year, two more of our journalists joined the Army, so we started doing fewer large-scale projects. In total, six people from the editorial staff are fighting.

In recent months, we have again written extensively about Russian disinformation, which has become more prevalent on various social networks, particularly Facebook. We made various infographics of shelling and used the data to describe various aspects of civilian life during the war.

The world is changing rapidly, and we can only hope to keep up.