The underground school. How Kherson teachers taught children Ukrainian curriculum during Russian occupation

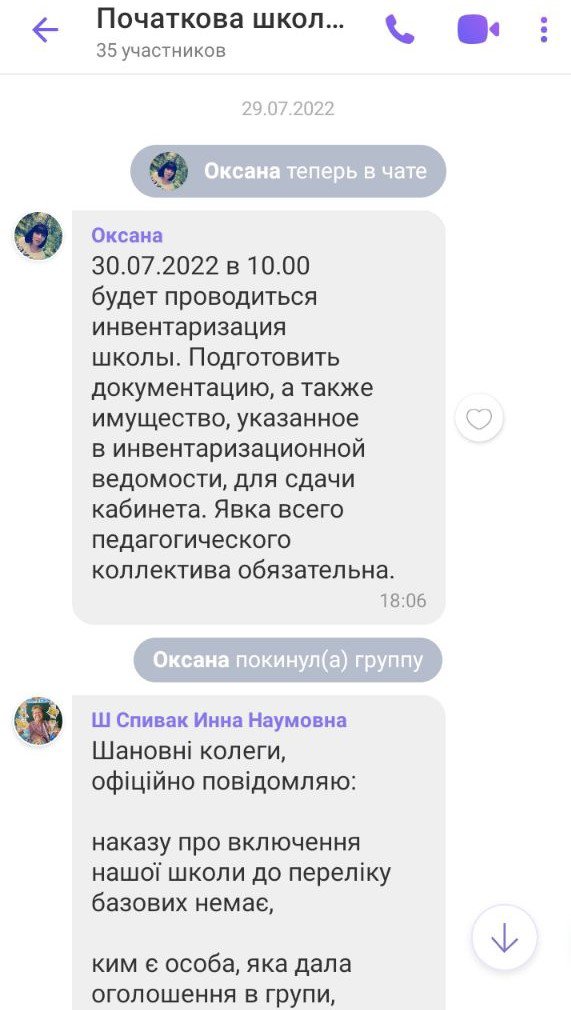

On July 29, a message in Russian was sent to the group chat of the teachers from Kherson secondary school No. 46: “On July 30, 2022, at 10:00 a.m., an inventory of the school will be conducted. You are requested to prepare the documentation and property items specified in the inventory list. The attendance of the entire teaching team is mandatory.”

Translated by Dmitry Lytov & Mike Lytov

Although no one from the team knew who wrote this message, everyone understood what it meant: the school was taken over by the Russians. But the team was not going to stop the work of the Ukrainian school, despite all the risks.

The story of school No. 46 in Kherson demonstrates how Russia put in practice the educational policies in the occupied territories of Ukraine: the forced Russification of children through threats and intimidation of parents and the complete obliteration of Ukrainian education.

Takeover of the school

The recent experience of the pandemic turned out to be very useful. Teachers and administration already had an established system of communication between themselves, as well as with students and their parents. All classes, as during the quarantine, took place remotely through Zoom.

Students and teachers, whenever possible, connected to joint sessions – either from occupied Kherson and the territories controlled by Ukraine or abroad. The workload of some teachers has increased several times – they had to fill in for those who were not able to conduct classes. But the children continued receiving education.

To prevent the Russian occupiers from ransacking the school, in May 2022 the teachers took some of the school equipment home. Then, for two months, school employees and parents of students patrolled the educational institution in turns to protect what was left from looting.

Anzhela Volobuyeva and Inna Spivak, school deputy directors, took up the organization of the educational process.

At the end of July, collaborators took over the school. According to school staff, the first to betray were the secretary and the librarian, who began to persuade the rest of the teachers and technical staff to switch to the enemy's side.

The librarian, who began to cooperate with the occupiers, contacted a former teacher from the school and, presumably, offered her to run a “new Russian school”. This woman, as she later told other teachers, met with the head of the occupation administration of Kherson, Volodymyr Saldo, and he appointed her as the new principal of the school.

On July 29, the school staff group chat in Viber received a message in Russian from an unknown woman. She ordered the entire team to come to the school on July 30 and hand over valuables. Anzhela Volobuyeva and Inna Spivak kicked out the author of the message from the chat and followed up with an announcement so that none of the teachers would come.

“All the teachers stayed at home,” says Volobuyeva. “The same message also came in the chat of the technical staff, which the secretary-collaborator created for recruitment. We didn't know about this chat and didn't send a message there to warn them to stay home. Due to this mistake, the janitor came to the school, right to the hornet's nest of collaborators. He sat, listened, and then told the ‘new administration’ that he would not cooperate with them. In those circumstances, it was a very brave act.”

Clash with collaborators

On August 1, teachers together with parents decided to come to the school to collect their personal belongings and try to remove the remains of the equipment.

“The new principal wouldn't let us in. She told me that she was the boss here now and was personally appointed by Saldo,” recalls Spivak. “But we broke through, thanks to our parents who came to support us. We managed to take only their work books and some personal belongings: scarves, shoes, etc.”

“We couldn't take the equipment,” said Volobuyeva. “Our former colleagues, now collaborators, were following us and grabbing our hands when we tried to pick some stuff up shouting that they would call the military security. We managed to take only personal belongings. Soon after that, soldiers with machine guns appeared at the school and we were not allowed there anymore.”

On August 1, teachers saw how many of their colleagues began to cooperate with the occupiers. Some of them left the Ukrainian school even earlier, and some continued to work on both sides and pretended as if nothing had happened.

They received salaries from Russia and vacation pay from Ukraine. But on August 1, the administration of the Ukrainian school severed labor relations with all those who sided with the occupiers, and now the special services have started an investigation.

“The [Ukrainian] state supported us. They paid less than before the Great War, but they still did,” says Volobuyeva. “That is why the behavior of traitors makes me so angry. If there was no money at all, I could understand someone who had to work under the enemy’s authorities in order to survive, to support themselves and their families. But since our state paid the money, it was nothing but greed. Yes, it was very scary, but we were not threatened with weapons, only some people just wanted to grab the better piece.”

Underground

On the eve of September 1, Spivak and Volobuyeva began to organize an underground education process. The deputy directors collected applications from parents who wanted to register their children for family or distance forms of education.

Parents who remained in the occupied territories were advised to take their documents from the school and tell the “Russian school” employees that they were planning to leave the city. The children’s personal files contained their residential addresses, so this was necessary to prevent the occupiers from knocking on the parents’ doors and forcing them to send their children to a Russian school.

So did Olena Tetereva, the mother of a 3rd-grader who studies at school No. 46. She decided not to leave Kherson, but absolutely refused to send her child to a “Russian school”.

The woman demanded the school to return her child’s personal file and explained to the “new administration” that she would be leaving the city. She was asked to return Ukrainian textbooks for the second grade and only then was allowed to receive the file.

Later, collaborators caught Olena already at work, in the hospital. The staff who agreed to cooperate with the Russians collected lists of workers with children in Kherson. She was asked if she was going to send her son to school. Olena avoided a direct answer — she said that she and her child were planning to leave or that she was still thinking about going to a “Russian school” and was not yet ready to give an unequivocal answer.

“I read in various Telegram channels that the Russian occupiers threatened parents who did not send their children to school,” Olena says. “Therefore, I could not state my position directly, but I absolutely refused the ‘Russian school’. My son is Ukrainian, so he will go to a Ukrainian school.”

The school also recommended that those who remained in Kherson write an application for family education so that the occupiers would not touch them if they found out that they were attending classes in a Ukrainian school.

But Olena chose distance learning for her child so that her son could maintain contact with classmates and teachers. She remembers that the boy sat at the laptop even during breaks between classes, talking with other children.

Another problem of the underground school was communication. Parents with children in Kherson had to use a VPN, because the Russians blocked access to many websites. The internet worked very poorly on many occasions, so students sometimes couldn't join classes, but the school supported them.

Olena says that the teachers created Google classes, where they wrote what classwork and homework should be done. So when her son could not connect to a distance lesson on Zoom, Olena connected to Google Classroom during her time-off and did the tasks together with her son.

Threats from the occupiers

Olena's fears were not unfounded: the Russians really did threaten some parents and teachers.

Inna Spivak said that one day her student’s mother called her for advice on what to do. This woman’s father worked at a bakery, and the boss threatened to fire him if he did not send his grandson to the Russian school. Under this pressure, the mother was forced to send the child to the occupiers’ “school”, but the latter also continued to study in Ukrainian on a family basis.

Another single mother was directly threatened by the occupiers. The woman worked in a store, the child was always with her. The Russian military used to shop in this store, and before the school year they forced the woman to send her child to their school. They said they would take away her parental rights if she didn't comply.

Teachers were also threatened.

Anzhela Volobuyeva remained in occupied Kherson, so she could not teach due to the order of the Ministry of Education and Culture. But she decided to conduct free consultations for 11th-graders to prepare them for the external examination in mathematics. The teacher was afraid that someone might find out about it and report her to the Russians.

“Teachers, principals, deputies from other schools told me that the Russians came to their homes, took the equipment, even their own, not the school’s equipment, mocked and intimidated them. I also had equipment from school at home, so I was afraid that they would come for me too. If someone on the street did not like the way you look at them, they could throw you ‘into the cellar’,” Volobuyeva says. “But our team was very lucky. No one threatened me, but I was admonished twice to work in a ‘Russian school’.”

A month of study

The occupiers offered “bonuses” to parents who sent their children to a “Russian school”: 10,000 rubles (about 145 US dollars). Also, high school students could enter lyceums and colleges of Kherson, captured by the Russians, without competition.

In the end, the training that the occupiers forced Ukrainian children to attend lasted only a month.

“In September, our school started working under the auspices of collaborators, but a few weeks later the children were released for the holidays. The Russians were preparing for their so-called referendum”, says Spivak. “And after that, the school was never opened, because the counteroffensive of the Ukrainian Armed Forces began.”

The Russians managed to enroll very few children in school No. 46 — there were 15 students in each class, and they only opened one class per school year. Subjects were taught by both technical and administrative staff, so this training was only for the sake of reporting.

Armed guards were constantly on duty near the school. The Russian military did not allow parents to enter the school even on September 1, when the celebration to mark the start of the school year was held in the assembly hall.

Olena Tetereva lived next to the school, and before the occupation, her son used to play in the school yard. But when armed soldiers appeared at the school entrance, the boy became afraid of the place and never went there again. And he had no one to play with – most of his classmates had left the city.

Olena said that she saw from the window how schoolchildren went to school at 8:00 a.m. and returned at 11:00 a.m. The occupiers brought their textbooks, but there weren’t enough of them for everyone. Two of Olena's neighbors sent their children to a “Russian school” out of fear, but their children studied without books.

These same neighbors told Olena that studying the Ukrainian language in the “Russian school” was optional. To study Ukrainian, they had to submit a separate application – almost like in the USSR.

At the end of September, the Russians closed the school and organized a voting station there for their “referendum” on its premises. For these four days, Kherson was empty – everyone was afraid to go outside, lest they be forced to vote for joining Russia.

And already in November, the school finally became Ukrainian again. However, the Russians never stopped tormenting the city – in December, due to Russian shelling, all the windows in the school were broken.

“We welcomed our guys in Kherson, we have been waiting so long for the Ukrainian forces to come,” says Anzhela Volobuyeva. “And together with the school, we keep going through all this shelling.”